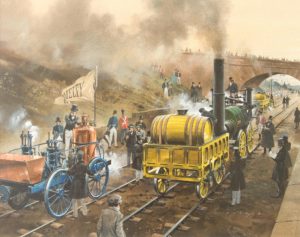

Arrive into Rainhill by train and you won’t be able to miss the glaring homages to the village’s locomotive heritage, and for good reason. The Rainhill Trials, which saw the launch and testing of Stephenson’s Rocket, had enormous implications for communications worldwide. Its impact on society as a whole was of a magnitude that is difficult to comprehend today; as Barrie Rushton of the Rainhill Railway and Heritage Society said, ‘before the Rocket, the fastest means of transport was a horse!’

2019 marks the 190th anniversary of the Rainhill Trials, which took place in October 1929.

The Rainhill Trials had one goal – to find the best method of hauling trains between Manchester and Liverpool. The directors of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway were split between those who thought winding engines would be required for the inclines at Whiston and St. Helens, and those who thought locomotives would do the job. The competitions rules stipulated that the winning locomotive must be capable of travelling at least 10 miles per hour while pulling a 20-tonne train. Engines had to ‘consume their own smoke’ and limit steam pressure in the boiler to ensure they could effectively go the distance. The engines would have to demonstrate their ability to make the 35 mile journey between the two cities along the only partially completed Liverpool and Manchester railway – at Rainhill, a small hamlet on the Turnpike Road.

In fact, the decision to use Rainhill as the location for the Trials was largely coincidental. The Liverpool & Manchester Railway began construction in 1826, and was originally going to travel through St. Helens and across estates belonging to the Earls of Derby and Sefton, but objections were raised to these plans and the railway was instead built through Rainhill – where the only level stretch of track was located. The original station was at Kendrick’s Cross, east of the present building, and the line’s diagonal placement necessitated the construction of the oddly-proportioned Skew Bridge which still stands today.

Designed by Robert Stephenson in Newcastle upon Tyne, the Rocket was one of five locomotives to compete in the Trials, along with Brandreth’s Cycloped, Ericsson & Braithwaite’s Novelty, Bustall’s Perseverance and Hackworth’s Sans Pareil (Unmatched). Not all of the locomotives in the Trials were steam powered. Cycloped was actually horse-drawn, a concept which fell flat when one of the horses collapsed through the wooden boards beneath it and had to be withdrawn from the race. Regardless, the horse had no way of keeping up with the steam engines, and was outdone by the other competitors.

Rocket combined many elements that other locomotives had started to introduce in one innovative package, using a blast-pipe exhaust which allowed the engine to self-regulate and a more effective boiler to power the engine on. Its name derives from a weapon used by the British military in the 1800s, not the spacefaring rocket of nineteenth century science-fiction as you might expect. Congreve artillery rockets were British in design, capable of travelling over 2,700 metres at great speeds, and were used during the Napoleonic Wars.

Still, the Rocket was certainly boundary defying, reaching a metaphorical stratosphere if not a literal one. True to its namesake, Rocket steamed away with a £500 win at the Rainhill Trials, reaching a top speed of 30 miles per hour and averaging 12 mph as it traversed the railway. The line itself eventually opened in September 1830 – the first full-scale inner-city railway to be exclusively powered by locomotives and offer both freight and passenger services.

Like many engineering feats of the era, Rocket’s success didn’t come without tragedy. When the railway officially opened, the locomotive was travelling to the since demolished Parkside Station near Newton-le-Willows to pick up the gathered dignitaries who were attending the opening. As William Huskisson MP descended from his own private train carriage, he was unable to reach the platform before Rocket collided with his leg – an injury which proved fatal.

Despite the accident, Rocket’s success was undeniable. Rainhill has always accepted and indeed embraced these inextricable links to the railway. Rocket features on village signposts leading into Rainhill; the 150 Trials Celebration Committee came together in 1977, going on to launch the Railway and Heritage Society out of the library and the carriage museum behind it; and the Model Railway Club continues to host regular exhibitions of their own miniature trains. Rainhill’s passion for locomotion is obvious – and this year will bring that passion to the forefront once again.

Rainhill is gearing up for the latest weekend-long celebration of the Trials. Parish Council Clerk Gillian Pinder already feels keen that the events celebrate Rainhill’s industrial heritage, bringing local schools and organisations together to commemorate the 190th anniversary.

‘The project will nurture the curiosity of younger generations, inspiring them to research further the development of rail transport on the first ever public railway for the transportation of passengers and freight between remote cities,’ she tells me. ‘It will bring back to life the excitement and anticipation of the previously untested and revolutionary engineering ideas.’

Preparations for Rocket’s anniversary celebrations are well underway – including the return of a replica Rocket to the area for the weekend. While the real engine is on display at the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester until September, a to-scale replica on loan from the National Railway Museum in York will bring Stephenson’s engineering back to life in the village. The colourful Rainhill Rocket will head a costumed parade through Rainhill from 1pm-2pm on the Sunday, complete with a marching band, floats and other vintage locomotives. A new heritage plaque is also set to be unveiled at Rainhill Station. Rainhill Gala will provide a fitting finale to the weekend on Monday 27th.

The weekend is filled with opportunities to learn more about Rainhill’s heritage. Exhibitions of railway memorabilia, vintage locomotives and related photography displays will take place around the village and at St. Ann’s Centre on View Road, while costumed actors will perform vignettes of events significant to the development of Rainhill, as well as offering guided tours around the village.

From Thursday, May 16 until Saturday, May 18, a performance of Arnold Ridley’s ‘Ghost Train’ by Rainhill Garrick Society. The play tells the story of six passengers stranded at a small Cornish wayside station, which is rumoured to be haunted by a ghost train. Despite warnings from the stationmaster, the group stay the night in the waiting room – until ghostly apparitions begin to materialise. The Ghost Train departs at 7:30pm at Rainhill Village Hall each night, and tickets for the performance are available from the Post Office and the Village Hall, or on 01744 813429.

Gillian hopes these immersive glimpses into Rainhill’s railway heritage will evoke ‘a sense of the danger, excitement and mystery surrounding the first people to travel in a “horseless carriage”’. Indeed, the Trials would have been seen as a sort of science-fiction; 190 years ago spectators covered 1.5 miles of track to get a glimpse of the steam engine to a ‘racecourse atmosphere’, with a band playing and plenty of opportunities to bet on the winner.

Heritage events aren’t the only things to get your teeth stuck into. Rainhill boasts a full calendar of family fun across the sunny month of May: and you don’t want to miss out.

For details of all activities, visit the Rainhill Rocket 190 website at www.Rocket190.org.uk or see the Facebook page @rainhill190.